“To be human is to be involved with cloth”, says Beverly Gordon, the author of Textiles: The Whole Story. And preserving the dresses conveying the stories of women first and foremost is the passion of Widad Kawar, historian and costume specialist in the Middle East, and one of the greatest collectors of traditional costumes in Jordan and Palestine. Some of the collector’s dresses were showcased at the Musée du quai Branly, on the occasion of the exhibition “The Orient of the Women as seen by Christian Lacroix.”

A great name in the world of fashion, Christian Lacroix was approached to participate in the exhibition in order to attract the attention of the media that have always ignored this age-old clothing art, now disappearing due to a lack of media coverage, regrets the historian. The use of globalized fashion clothing, jeans, is the second cause of this disappearance, which began in the 1960s, she explains, along with the appearance of synthetic fabrics, machines and the disappearance of vegetable dyeing. The production of indigo is no longer natural but now synthetic and widely used in the Arab world, and used to dye jeans.

Finally, the appearance of dark and austere clothing, the “Islamic dress”, zayy islâmi or “sectarian habit” which completely covers the body has replaced the traditional costume and made us forget the richness of this savoir-faire of sewing – embroidery – and the woman is now hidden behind the veil, deplores the collector and Hana Chiniac, head of the North Africa and Near East Heritage Unit at the Quai Branly Museum, and curator of the exhibition, as well as Véronique Rieffel, the author of Islamania, From the Alhambra to the Burqa, a story of artistic fascination, “a work between essay and art book, a counter-dictionary of received ideas on Islam.

BETHLÉEM, “THE PARIS OF PALESTINE”

Born in Palestine and now living in Jordan, Widad Kawar was mainly interested in the sewing skills pertained in these two countries, while broadening her curiosity to neighboring countries to better compare traditional clothing production in the “Fertile Crescent” region, from northern Syria to the Sinai desert.

In Bethlehem, Widad Kawar grew up from her childhood surrounded by the embroidery know-how that made the city’s reputation. “This Paris of Palestine”, as its inhabitants call it, then cultivates the tradition of handmade embroidery and weaving. The city “sets the tone for fashion in villages.”At the beginning of the 20th century, Bethlehem’s dress was indeed described as ‘malak’, which means ‘royal’, because of its sumptuousness in terms of colors and embroidery that it was described as the ‘queen’ of the dresses of all Palestine, she explained. It is now a rare piece for collectors, as women usually kept the most beautiful one to be buried with. By 1920, making the Malak dress for women from other parts of Palestine had become a lucrative business. The weavers, dressmakers and embroiderers of Bethlehem became famous. In spite of the interdependence between the major cities of Palestine, the surrounding rural areas with the Syrian textile industry was shattered by the 1948 war and the subsequent occupation of Palestine, explains Widad Kawar. The costumes have remained a symbol of Palestinian culture and women’s creativity.

EMBROIDERIES THAT TELL STORIES OF WOMEN

Traditional embroidery skills on dresses are passed down from generation to generation in villages in Palestine, explains Margarita Skinner*, head of humanitarian missions in the Middle East. The motifs were perpetuated from mother to daughter, each generation slightly modifying them and renewing their inspiration.

“They can be read like books; because each village has its own color and patterns that have a name. The motifs will also inform other women of the geographical origin and social status of the woman who wears them (young girl, married woman, widow…), says Christophe Moulherat*, Preventive Conservation Officer at the Musée du quai Branly.

And the names themselves evoke a story, among the most common ones are drawings referring to fauna: from a bird of paradise to a cow’s eye; fields and gardens are evoked by orange blossoms, chickpeas and raisins. There are also 15 modes of representation and names for the moon and stars, while the palm tree is a symbol of longevity. The regions in Palestine will then develop their own style. (photo: Bedouin woman of the Tiyaha Tribe, Quai Branly Museum)

Only women are embroiderers. They began their apprenticeship at the age of six in order to master the art of embroidery necessary to make their trousseau before their wedding. They must master the different embroidery techniques, but above all become familiar with the repertoire of local designs and their arrangement in dresses, explains Christophe Moulherat. Mothers make costumes for their daughters; daughters make small pieces for the house. On the occasion of a wedding or a birth, a new dress is made by the elders.

“The making of the wedding dress could take several years, explains Christophe Moulherat, often because of the price of the silk yarn.”

The embroidery thread is most often made of cotton, sometimes silk, rarely wool. Synthetic yarns, spun with silver or gilded silver are also used. Flat, knotted, looped stitches are used. Flat stitches most often consist of attaching a gold or silver yarn to the fabric through a stitch placed at regular intervals.

PRESERVING THE MEMORY OF THESE DRESSES AND THE LIVES OF THESE WOMEN

Widad Kawar became interested in these traditional clothes in the 1950s, which she collected intermittently. Then came 1967 – a turning point in the history of the region and for the collector who was then on the lookout for these scattered clothes, as were the women scattered in refugee camps. Village life is no more.

Driven by the desire to preserve these clothes and the history of each of the women who embroidered them, with love, in order to prepare the ceremonial garment, Widad Kawar travelled through the refugee camps, buying the dresses from the women. The welcome is enthusiastic. Ex-villagers who have become refugees come to Widad Kawar on their own to sell their dresses that have become useless in the camps, and are delighted to know that their precious clothes and life history will be preserved. Embroidered dresses from childhood will last over time. Widad Kawar knows everything about each dress, the woman who made it and her life story.

Driven by the desire to preserve these clothes and the history of each of the women who embroidered them, with love, in order to prepare the ceremonial garment, Widad Kawar travelled through the refugee camps, buying the dresses from the women. The welcome is enthusiastic. Ex-villagers who have become refugees come to Widad Kawar on their own to sell their dresses that have become useless in the camps, and are delighted to know that their precious clothes and life history will be preserved. Embroidered dresses from childhood will last over time. Widad Kawar knows everything about each dress, the woman who made it and her life story.

One story particularly made a deep impression on Hana Chidiac in 2007, when she was on her way to Aman to meet Widad Kawar: “a Palestinian woman of a certain age came to her home and ask her to buy her traditional festive dress that she could no longer wear because, she said, according to the rules of Islam “a pious woman must not go out dressed in colorful clothes”. It was her wedding dress she had embroidered.

In this context, the collector continues her exploration of the identity issues of oriental women through the use of traditional clothing by also raising public awareness, through her articles and books dedicated to these women’s stories and their sewing skills : “these artists without knowing it”, as she called them. Threads of identity is her latest book.

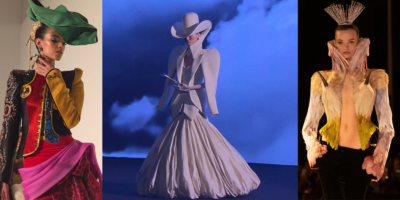

The identity issues of oriental women, which are recurrently raised by foreigners, have been also explored by fashion designers in the West. They have dealt with the theme of the veiled woman, recalls Véronique Rieffel, quoting Hussein Chalayan’s fashion shows, which once brought veiled women and completely naked women side by side. She mentions artworks by the visual artist Majida Khattari’s performances entitled VIP (Voile Islamique Parisien), which approach contemporary art with the codes of haute couture to better illustrate the complexity of the debate between these two extremes, explains the artist, on the one hand the veiled woman, on the other hand the “doll woman”.

THE INSTITUTE OF ISLAMIC CULTURES

Islamania is more than a book, it is a program to raise awareness of Islamic cultures with conferences and an exhibition by Martin Parr on the Parisian district of La Goutte d’Or, presented until July 2. His mischievous and English perspective – far from the French polemics on French identity and immigration issues – motivated the choice of the photographer for this project. The photographs appear more conventional than usual with portraits of residents staged in their neighborhood where the institute is located. A very pleasant place to immerse yourself in this part of Paris that you hear more about than you visit…

Islamania is more than a book, it is a program to raise awareness of Islamic cultures with conferences and an exhibition by Martin Parr on the Parisian district of La Goutte d’Or, presented until July 2. His mischievous and English perspective – far from the French polemics on French identity and immigration issues – motivated the choice of the photographer for this project. The photographs appear more conventional than usual with portraits of residents staged in their neighborhood where the institute is located. A very pleasant place to immerse yourself in this part of Paris that you hear more about than you visit…

SOME REINTERPRETATIONS OF ORIENTAL CLOTHING IN EUROPE FOR THE PLEASURE OF THE EYES!

In her book, Véronique Rieffel discusses the influence of oriental clothing, particularly for couturiers who sought to break out of the uniform male Western clothing. In her book, the author refers to couturiers such as Lacroix or Gaultier who curated the Men In Skirts exhibition at the Victoria&Albert Museum in London and the Metropolitan in New York, or years away when Paul Poiret was the costume designer for the 1913 play Le Minaret. Below, pieces reinterpreting the sarouel and caftan for women with the autumn/winter 09 collection from Givenchy and the spring/summer 2011 collection from Missoni, including as well as the pieces by Paul Poiret cited by Véronique Rieffel. The couturier was so impressed by these costumes that he later made them the theme of a fabulous Persian evening.

NOTES :

Le site de l’exposition L’Orient des Femmes vu par Christian Lacroix, Musée du quai Branly

Articles de Widad Kawar, Christophe Moulherat, Margarita Skinner dans Le catalogue de l’exposition L’Orient des Femmes vu par Christian Lacroix, Musée du quai Branly

Interview video of the curator of the exhibition, Hana Chidiac by Nicole Salez

The Institut des Cultures d’Islam in Paris website

Islamania, by Véronique Rieffel / Beaux Arts Editions & Institut des Cultures d’Islam

Thanks for sharing very informative for me

I’ll glad you’ve found the article very informative for you: it was such a pleasure meeting with Widad Kawar and discovering her wonderful dedicated actions, and share it all here.